1

1 1

1

By Cecile Mantovani and Denis Balibouse

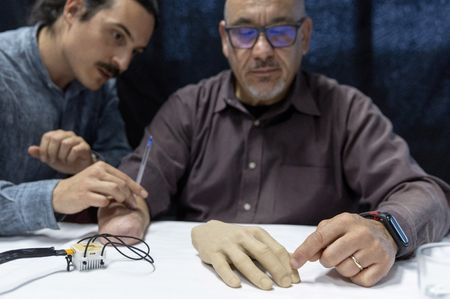

GENEVA (Reuters) – Fabrizio Fidati, who lost his right hand in an accident 25 years ago, had not experienced the sensation of temperature in his missing digits until trials for a bionic technology unlocked the cool of iced water and heat of a stove burner for him.

Eventually, the researchers hope it could lead to a more natural feeling of loved ones when he is wearing his prosthetic.

With thermal electrodes placed on the skin of their residual arm, amputees such as Fidati reported feeling hot or cold sensations in their phantom hand and fingers, as well as directly on the arm, according to the trials by the École polytechnique fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL).

The 59-year-old Italian is among 27 amputees who took part in the trials, with 17 of them reporting a successful test.

“The first time I took part in the experiment, I felt like I had rediscovered feeling in my phantom hand,” he said.

Those tested have also been able to differentiate between plastic, glass and copper, pointing to where they feel the sensations on images of a hand.

“By stimulating specific parts of the residual arm of the amputees, we could induce sensation in the missing phantom hands,” said Solaiman Shokur, a senior scientist neuroengineer at EPFL who co-led the study, published in the journal Science.

“What they feel in this phantom hand is similar to what they feel on their intact hand.”

A woman who also took part the study, Francesca Rossi, said she had previously been able to feel tingling in her missing hand when she touched the end of her arm, but said: “Feeling the temperature variation is a different thing, something important … something beautiful.”

The technology, which has been tested for more than two years, does not need to be implanted. It can be worn on the skin and combined with a regular prosthetic.

Silvestro Micera, who co-led the study with Shokur, said they now wanted to test the device on a larger scale before combining it with other technologies to improve tactile sensations in amputees.

“We think that we could give people a better sense of embodiment of their hands and maybe even give them the possibility to feel their loved ones in a much more natural way,” Shokur added.

Fidati said that beyond helping amputees with daily tasks such as cooking, the technology could open the door for him to feel the warmth of others.

“There is also a social aspect that is important,” he said. “When I meet someone and shake his hand, I expect to feel heat.”

Micera, a professor at EPFL and Sant’Anna School of Advanced Studies, said: “Temperature feedback is essential for relaying information that goes beyond touch, it leads to feelings of affection. We are social beings and warmth is an important part of that.”

(Reporting by Cécile Mantovani and Denis Balibouse; Writing by Gabrielle Tétrault-Farber; Editing by Alison Williams)