1

1 1

1

By Tom Balmforth

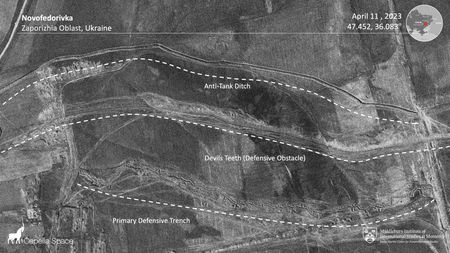

(Reuters) – The anti-tank ditches near Ukraine’s occupied southeastern town of Polohy stretch for 30 km (19 miles). Behind are rows of concrete “dragon’s teeth” barricades. Further back are defensive trenches where Russia’s troops will be positioned.

The defences visible in satellite imagery taken by Capella Space are part of a vast network of Russian fortifications sweeping down from western Russia through eastern Ukraine and on to Crimea built in readiness for a major Ukrainian attack.

Thousands of Ukrainian troops have been training in the West to use different military assets on the battlefield in a combined way ahead of a counteroffensive Ukrainian officials say will come when its forces are ready.

Reuters has reviewed satellite images of thousands of defensive positions inside both Russia and along Ukrainian front lines that show it is most heavily defended in the southern Zaporizhzhia region and the gateway to the Crimean Peninsula.

Six military experts said the defences, mostly built in the wake of Ukraine’s rapid autumn advances, could make it harder for Ukraine this time and that progress would hinge on its ability to carry out complex, combined operations effectively.

“It’s not the numbers for the Ukrainians. It’s can they do this kind of warfare, combined arms operations?” said Neil Melvin, an analyst at the Royal United Services Institute (RUSI). “The Russians have shown they can’t do it and they’ve gone back to their old Soviet method of attrition.”

A Ukrainian counteroffensive could change the dynamics of a war that has slowed into a bloody battle of attrition and military experts say the length of the front could stretch Russia’s defences.

If Kyiv can wrest back control of the south, it could regain unimpeded access to its Black Sea export routes at a time when Russia has signalled it may slam the grain corridor shut.

Ukraine may not receive another large injection of armoured hardware from the West any time soon, which is putting pressure on Kyiv to retake as much land as possible in case military support begins to wane, military experts say.

“We’ve cleaned out most of the stocks in the West,” said Melvin. “It’s going to take some years to rebuild. I think this is (Ukraine’s) big opportunity to press on.”

Ukraine’s Defence Ministry did not respond to a written response for comment about any counteroffensive.

LAND CORRIDOR

Ukraine has vowed to take back all the territory occupied by Russia, an area roughly the size of Bulgaria, but officials are reluctant to disclose any information that could help Moscow.

The West has sent scores of modern battle tanks and infantry fighting vehicles to serve as the vanguard of an assault, along with bridging equipment and mine clearance vehicles.

That’s why Russia has been digging extensive, layered fortifications to ensure its troops will be far more entrenched than when they were chased out of Ukraine’s northeast and Kherson city, the satellite images show.

The pictures analysed by Reuters show much of the Russian construction occurred after November, when its forces pulled back from Kherson city in the south and both sides looked to consolidate positions during the winter months.

Stretching hundreds of kilometres, the military experts say the defences mark areas where Russia expects to be attacked, or sees strategic significance in holding onto territory.

Russia’s defence ministry did not respond to questions about the defences and its ability to repel a counteroffensive.

According to the satellite images, Russia’s positions are most concentrated near the front lines in the southeastern Zaporizhzhia region, in the east and across the narrow strip of land connecting the Crimean Peninsula to the rest of Ukraine.

The military experts all expected the main thrust of a counteroffensive to be in the south, even though the heaviest fighting in recent months has been concentrated in the east, and in particular around the city of Bakhmut.

Last week, Russian President Vladimir Putin made a rare trip to the Kherson region in what some observers saw as a signal of its strategic importance.

Oleksandr Musiyenko, a military analyst in Kyiv, said the south was strategically vital for Ukraine.

Besides disrupting the land corridor from Russia to occupied Crimea, making deep inroads into the south could bring the peninsula into artillery range, he said.

The diamond-shaped peninsula seized from Ukraine in 2014 is home to the Black Sea Fleet which Russia uses to project power into the Middle East and Mediterranean and – over the last 14 months – rain down cruise missiles on Ukraine.

The south is also home to the Zaporizhzhia nuclear power plant, Europe’s largest, which has been occupied since March last year and idle since September. It used to supply a fifth of Ukraine’s electricity needs.

HUGE DIGGING EFFORT

The town of Polohy pictured in Capella Space’s satellite images, lies in the Zaporizhzhia region, a key gateway for Ukraine to bear down on the largely flat south.

The rest of the south lies beyond the Dnipro River, a huge natural barrier for Ukrainian forces to overcome.

“I traced ditches and trenches running from the eastern bank of the Dnipro south of Vasylivka all the way to Fedorivka, which is to say they run across Zaporizhzhia (Region),” said John Ford, research associate at the Middlebury Institute of International Studies at Monterey.

He estimated that defensive section alone stretched for 120 km.

The anti-tank ditches are deep and wide enough to obstruct advancing tanks and armoured vehicles. Then come concrete “dragon’s teeth” that serve as pyramid-shaped barricades. The manned trenches lie about a kilometre behind the ditches.

Besides the ditches, barricades and zig-zag trenches, Russia’s defensive lines will also include minefields, razor wire and camouflaged weapons positions.

And in the case of Polohy, Russia has constructed two distinct defensive lines, one to the north and one to the south.

Overheads of the Zaporizhzhia area seen by Reuters show some towns, such as Tokmak and Bilmak, have been encircled by fortifications. Trenches have been dug along roads, outside other settlements and at the city airports of Melitopol and Berdiansk. The north of Crimea has also been fortified.

Brady Africk, an open-source intelligence researcher and analyst at the American Enterprise Institute, said he had mapped fortifications from western Russia to Crimea, with construction starting in earnest after Russian troops abandoned Kherson city.

“That spurred a huge digging effort, especially across southern Ukraine, where the ground is quite flat,” he said.

BATTLEFIELD OBSTACLES

Despite the web of defences, four experts said Russia would be stretched by the length of the front, a vulnerability Kyiv would seek to exploit with feints, distractions, surprise and operational speed.

Musiyenko said Ukraine could use Western-supplied vessels to launch assaults on the Kherson region from across the Dnipro that would serve as decoys – or full-fledged attacks. That could force Russia to divert troops from elsewhere.

“Battlefield obstacles are only obstacles so long as they are guarded by capable troops,” said Middlebury’s Ford.

Musiyenko estimated that Ukraine would have a force of between 100,000-110,000 for an attack, including eight assault brigades with a total of 40,000 troops.

Russia has not said how many troops it has in Ukraine, or within its borders ready to deploy.

Ukrainian and Russian officials have reported on Telegram messenger a series of explosions over the last month in Melitopol, Zaporizhzhia region’s main occupied city.

Musiyenko said Ukraine was targeting logistics nodes as it did before recapturing Kherson city.

Wrecking Russian supply lines would render its trenches weak, he said: “Fortified positions are effective if you have ammunition, rounds, weapons that you can defend with.”

A leaked U.S. intelligence document dated Feb. 28 seen by Reuters said the West had committed 200 tanks to Ukraine. Army chief Valeriy Zaluzhnyi said in December he needed 300 to defeat Russia, along with other vehicles and artillery.

Those same documents also said Ukraine faced acute shortages of air defences, which could become a problem if Kyiv’s forces advance rapidly and need protection from aerial bombardments.

(Additional reporting by Idrees Ali and Jonathan Landay in Washington and Gerry Doyle in Singapore; Editing by Mike Collett-White and David Clarke)