1

1 1

1

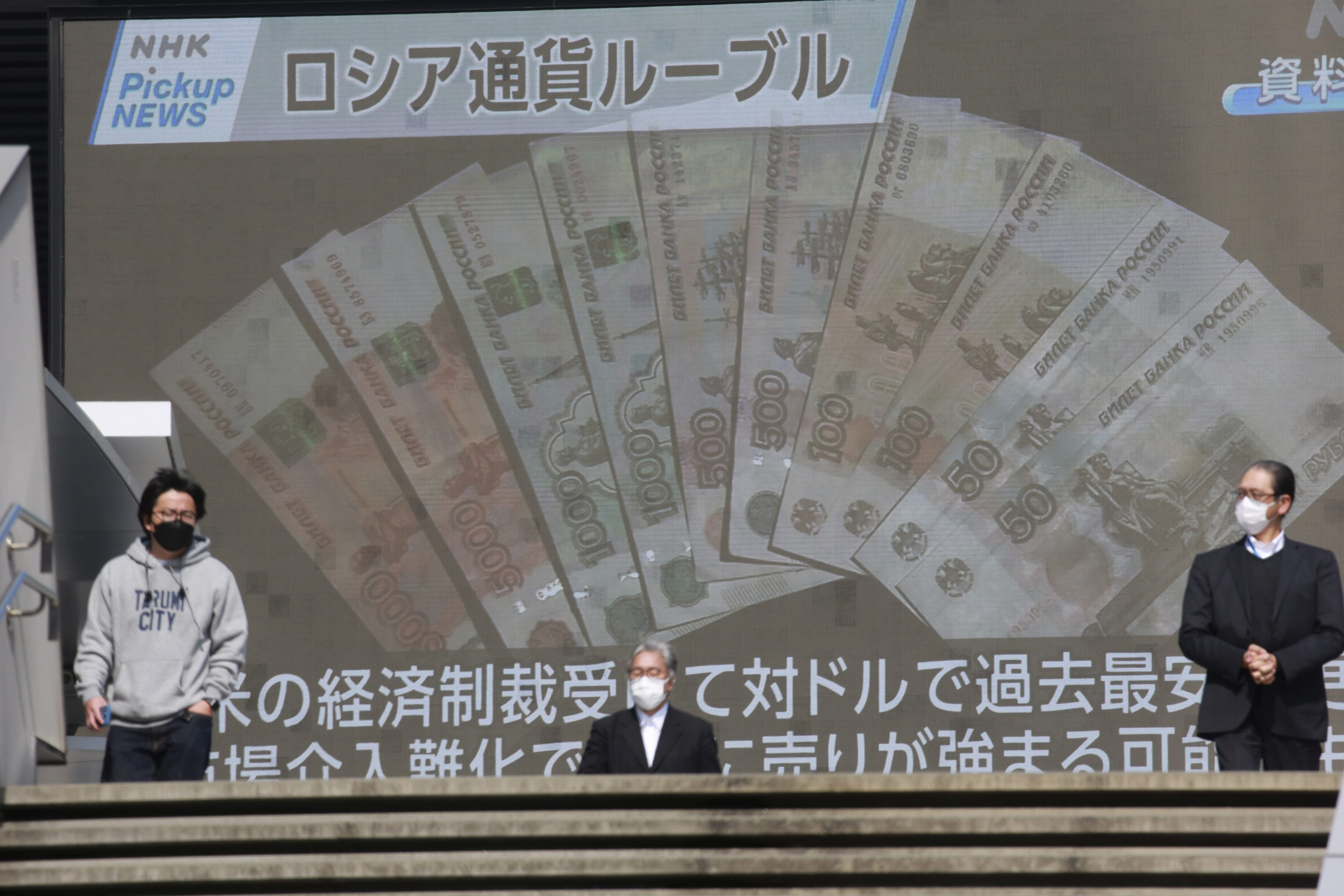

LONDON (AP) — Russia’s central bank has managed to stabilize key aspects of the economy with severe controls, artificially propping up the ruble to allow it to rebound to levels seen before the invasion of Ukraine even as the West piles on more sanctions.

That became evident as central bank of Russia said Friday that it was lowering its benchmark interest rate and said more rate cuts could be on the way. The decision indicates it thinks strict capital controls and other strict measures are stabilizing Russia’s currency and financial system despite severe pressure from U.S. and European sanctions.

The bank lowered its benchmark rate from 20% to 17%, effective Monday. The interest rate cut reflected “the changed balance of risks” among inflation, economic growth and banking system stability, the bank said.

It had raised the rate from 9.5% on Feb. 28, four days after the invasion, as a way to support the ruble’s plunging exchange rate. A currency collapse would worsen already high inflation for Russian shoppers by ballooning the cost of imported goods.

The ruble fell from 79 to the dollar the day before the invasion to as low as 139 to the dollar. But it has since recovered to around 77 rubles to the dollar in very limited trading, bolstered by drastic measures such as forcing companies to exchange 80% of foreign currency for rubles and barring foreign investors from selling out of their ruble holdings.

Russia has pressed buyers of its oil and gas to pay in rubles, without much success, although Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orban has expressed that he would be willing.

The bank said weekly price data showed “a substantial slowdown in the pace of price increases, partly as a result of the dynamic of the ruble’s exchange rate.” The official inflation figure for February was 9.2%.

The bank’s statement “allows for the possibility for a continuation of rate decreases at coming meetings.”

Western sanctions have dealt a severe blow to the economy, cutting major banks off from international transactions, freezing central bank reserves and leading many Western companies to abandon their businesses in Russia.

Since an initial round of sanctions over Russia’s annexation of Ukraine’s Crimea region in 2014, the Kremlin has tried to insulate its economy from financial penalties by encouraging companies to source parts locally and banning food imports from Europe to encourage local production.