By James Davey

ROYDON, England (Reuters) – In a small corner of south-east England, vast glasshouses stand empty, the soaring cost of energy preventing their owner from using heat to grow cucumbers for the British market.

Elsewhere in the country growers have also failed to plant peppers, aubergines and tomatoes after a surge in natural gas prices late last year was exacerbated by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, making the crops economically unviable.

The hit to UK farms, which need gas to counter the country’s inclement weather, is one of the myriad ways the energy crisis and invasion have hit food supplies around the world, with global grain production and edible oils also under threat.

In Britain it is likely to push food prices higher at a time of historic inflation, and threaten the availability of goods such as the quintessentially British cucumber sandwich served at the Wimbledon tennis tournament and big London hotels.

While last year it cost about 25 pence to produce a cucumber in Britain, that has now doubled and is set to hit 70 pence when higher energy prices fully kick in, trade body British Growers says.

Regular sized cucumbers were selling for as little as 43 pence at Britain’s biggest supermarket chains on Tuesday.

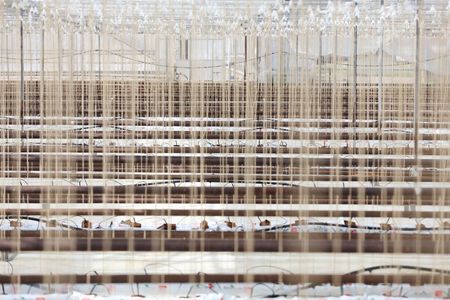

“Gas prices being so sky high, it’s a worrying time,” grower Tony Montalbano told Reuters, while standing in an empty glasshouse at Roydon in the Lea Valley where for 54 years three generations of his family have farmed cucumbers.

“All the years of us working hard to get to where we are, and then one year it could just all finish,” he said.

All 30,000 square metres of glasshouse at his Green Acre Salads business, which supplies supermarket groups including market leader Tesco, Sainsbury’s and Morrisons, are currently empty.

Montalbano, whose grandfather emigrated from Sicily in 1968 and started a nursery to provide local stores with fresh cucumbers, decided not to plant the first of the year’s three cycles in January.

SOARING COSTS

Last year he paid 40-50 pence a therm for natural gas. Last week it was 2.25 pounds a therm, having briefly hit a record 8 pounds in the wake of Russia’s invasion.

Fertiliser prices have tripled versus last year, while the cost of carbon dioxide – used both to aid growing and in packaging – and hard-to-attain labour have also shot up.

“We are now in an unprecedented situation where the cost increases have far outstripped a grower’s ability to do anything about them,” said Jack Ward, head of British Growers.

It means a massive contraction for the industry, threatening Britain’s future food security, and further price rises for UK consumers already facing a bigger inflation hit than other countries in Europe following Brexit.

UK inflation hit a 30-year high of 6.2% in February and is forecast to approach 9% in late 2022, contributing to the biggest fall in living standards since at least the 1950s.

The National Farmers’ Union says the UK is sleepwalking into a food security crisis. It warns that UK production of peppers could fall from 100 million last year to 50 million this year, with cucumbers down from 80 million to 35 million.

In winter, the UK has typically imported around 90% of crops like cucumbers and tomatoes, but has been nearly self-sufficient in the summer.

The Lea Valley Growers Association, whose members produce about three-quarters of Britain’s cucumber and sweet pepper crop, said about 90% did not plant in January, while half have still not planted and will not plant if gas prices remain high.

“There’s definitely going to be a lack of British produce in the supermarkets,” association secretary Lee Stiles said. “Whether there’s a lack of produce overall depends on where and how far away the retailers are prepared to source it from.”

Growers in the Netherlands, one of Britain’s key salad suppliers, face similar challenges and have reduced exports.

Spain and Morocco do not heat their glasshouses to a large extent, but delivery to the UK in chilled lorries adds time and cost.

Joe Shepherdson of the UK’s Cucumber Growers Association said those growers that have planted are using less heat, but that reduces production and increases the risk of disease.

PRESSURE ON PRICES

Britain’s biggest supermarket groups, including Tesco, Sainsbury’s, Asda and Marks & Spencer, acknowledge the pressures in the market but say they are confident about supply, stressing their long-term partnerships with growers.

How far the increase in production costs will translate to higher prices on the shelf depends largely on whether supermarkets opt to absorb the difference themselves, or pass it on to consumers.

Smaller retailers buying from the market may struggle.

“Any cut in production from suppliers would undoubtedly put further pressure on prices,” said Andrew Opie, director of food and sustainability at retail industry lobby group the British Retail Consortium.

Growers want help from the government. They have lobbied for tax and levies on gas to be removed, but finance minister Rishi Sunak did not mention it in his spring budget last week.

Despite the dismal backdrop and after much soul-searching, Montalbano will plant a crop next month, fearing the loss of future contracts if he does not. He may gamble on the British weather, and grow his plants “cold”, with little or no heat.

“I feel like I have no choice, because if I don’t, then I lose my place,” he said, in a glasshouse that in a normal March would be packed with bushy green cucumber plants.

“Am I going to make anything out of it? I’ll be quite happy to break even this year,” he said.

(Reporting by James Davey; Editing by Kate Holton and Jan Harvey)