By Sarah Marsh and Andreas Rinke

BERLIN (Reuters) -Germany on Thursday published its first and long-awaited China strategy which was unflinching in its appraisal of Beijing’s “increasing assertiveness” but vague on policy measures to reduce critical dependencies.

The 64-page document comes amid a broader push in the West to reduce strategic dependencies on a China – which policymakers have labelled “de-risking” – amid concerns about Beijing increasingly seeking to assert its hegemony in the Indo-Pacific.

There is particular concern in Germany about the impact of this de-risking strategy on an economy already in recession given its strong business ties with China, which became the country’s single biggest trade partner in 2016.

German companies and industry associations – some of which had warned against moving away from China too abruptly – welcomed the strategy that did not lay out any binding targets or requirements for them.

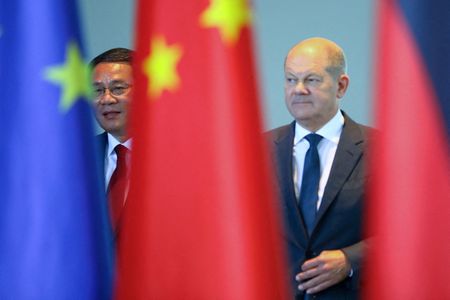

“China has changed. As a result of this and China’s political decisions, we need to change our approach to China,” said the document, which was agreed by the cabinet on Thursday after months of wrangling within Chancellor Olaf Scholz’s three-way coalition.

China remained an indispensable partner to tackle global challenges such as climate change and pandemics, it said.

However, it was also increasingly assertive in its attempts to change the rules-based international order with consequences for global security.

As such Germany would continue to strengthen its military presence and cooperation with partners in the Indo-Pacific, it said, warning that the status quo of the Taiwan Strait may only be changed by peaceful means and mutual consent.

“Military escalation would also affect German and European interests,” the strategy said.

Germany would expand its close relations with Taiwan, a self-ruled island China claims as its own, while continuing to adhere to the “one China policy”, which recognises the government of the People’s Republic of China as the sole legal government of China. It also said it supported the “issue-specific involvement” of Taiwan in international organisations.

China’s decision to expand its relationship with Russia also had immediate security implications for Germany, it said, noting Beijing lacked credibility on its support for Ukrainian sovereignty given its embrace of Russian narratives.

Analysts said the strategy, which underscores the need for close cooperation with the European Union on China, sent a clear message that Germany’s approach to the country had changed, after years of prioritising economic interests and overlooking geopolitical concerns.

“But there are questions around implementation”, said Noah Barkin, Europe-China expert at Rhodium Group, a U.S.-based research firm.

“Berlin is speaking loudly but it is wielding a small stick. Chancellor Scholz has made clear that he sees a very narrow role for the government when it comes to de-risking.”

DE-RISKING CONCEPT ‘TOO VAGUE’

At now nearly 300 billion euros ($325 billion) in imports and exports, China is a core market for top German companies including Volkswagen, BASF and BMW.

The strategy urged companies to take geopolitical risks into account in their decision making and said it would hold confidential talks with companies particularly exposed to China about their risk analyses.

It was reviewing whether state measures like export guarantees were reinforcing excessive dependencies and consulting whether it should develop more instruments to help reduce risks.

“The concept of de-risking is still too vague,” said Juergen Matthes, of the German Economic Institute, IW. “We need a clear identification of really critical dependencies and the government should regularly monitor whether de-risking on this basis is actually advancing.”

China’s embassy in Germany said on Thursday it hoped Germany would be rational and objective going forwards.

“Forcibly ‘de-risking’ based on ideological prejudice and competition anxiety will only be counterproductive and artificially intensify risks,” it added.

Separately, the strategy said the government would review its export control lists against the backdrop of new technological developments for example in cybersecurity and surveillance, to ensure German goods did not “encourage systematic human rights violations in China” or support further military rearmament.

It also backed the idea of potentially screening outbound investment controls on cutting-edge technology with military use – an idea the EU Commission is pursuing.

“We acknowledge that … appropriate measures that are designed to counter risks connected with outbound investment could be important as a supplement to existing instruments for targeted controls of exports and domestic investments.”

(Reporting by Sarah Marsh, Andreas Rinke, Matthias Williams, Friederike Heine, Miranda Murray, Rachel More in Berlin and Ethan Wang in Beijing; Editing by Rachel More, Alex Richardson and Nick Macfie)