1

1 1

1

By Joe Cash

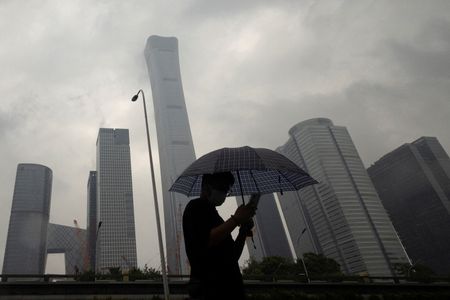

BEIJING (Reuters) – China is struggling to revive foreign investment in its financially battered cities and provinces as foreign firms remain wary of political risks and new incentives fall far short of sweeteners once used to attract overseas money.

With their coffers depleted after an economically bruising pandemic and property crisis, local authorities have been racing to find new revenue sources, with foreign investment particularly coveted.

Premier Li Qiang in March declared China open for business again, and since then provinces and cities from Sichuan to Chaozhou have sent delegations across the globe to pitch and invited investors to rare symposiums.

However, foreign industry executives and lobbyists say the incentives many local governments now offer are far less attractive than they were a decade ago, when companies could easily win subsidies or free land use and the regulatory environment seemed more predictable.

“Clearly the China-side is very much getting on the front foot with international engagement,” said Kiran Patel, senior director at the China-Britain Business Council. He cited five meetings between their London office and delegations from Chinese local governments in late June.

But “there’s still a lot of work to do in terms of warming up or reheating interest in China,” he warned.

The charm offensive contrasts with Beijing’s more hawkish overtures about dominance in supply chains and President Xi Jinping’s increased focus on national security.

Dollar-denominated foreign direct investment (FDI) fell 5.6% in January-May from the same period last year, despite the end of strict COVID curbs, as the post-pandemic recovery in the world’s second-largest economy faltered.

China’s Ministry of Commerce did not respond to a request for comment.

BENEFITS, NOT INCENTIVES

Noah Fraser, managing director of the Canada China Business Council, said his organisation had also been on the receiving end of a “charm offensive” from municipal, provincial and regional authorities, but that his understanding from most of them was that cash would not be forthcoming and projects would need to be self-financed.

“They’ll be friendly, they’ll be open minded, but I don’t suspect that they have a great deal of financial capital to move with,” he said. “So I think any equity or any assets will be…in the relationships and permissions that get rid of the red tape.”

Senior executives from three large Western companies that Reuters spoke to on the condition of anonymity said they were similarly unconvinced after discussing prospective investment with local authorities.

“(The incentives) are not worth engaging our finance team over, it’s public affairs work, as it’s a conversation we’re having with the local government, but it’s not going to affect the company’s investment or operational decisions,” said one of the executives.

He added that while in the past his company had been offered enterprise tax waivers and deals on land to put in fresh investment, an eastern Chinese government had recently only offered him a deal on personal income tax for their top executives amounting to 6 million yuan.

“I wouldn’t say its an incentive. It’s a benefit. But would our company stay in China forever for this 6 million yuan? No.”

PART OF THE SYSTEM

Local authorities carry out a delicate balancing act when courting foreign investment and dealing with critical questions about Xi’s security policies.

Many foreign companies have expressed concerns over the changing business environment in China, which in recent years has been marked by a crackdown on consultancies affecting how investors can perform due diligence, as well as new data and anti-espionage laws.

Analysts say there is now very little tolerance for deviation from Chinese Communist Party thinking on business, which has forced many foreign firms to rethink their approach to China.

“I do think (Li Qiang) wants and intends to bring inbound investment back, but he’s someone who’s loyal and so should he be asked to lock down Shanghai again or do anything that isn’t business friendly, he would,” said Agatha Kratz, director at Rhodium Group, a China-focused consultancy.

One of the three executives, whose employer is a foreign automaker, said he had been surprised by how officials had repeatedly raised Xi’s policies on self-reliance and self-strengthening in a recent meeting in a southern Chinese city.

“As far as the macro situation is concerned, local governments can’t do anything to reassure foreign investors. Actually, they are part of the system,” he said.

(Reporting by Joe Cash; Editing by Brenda Goh and Sam Holmes)