1

1 1

1

By Ahmed Rasheed and Timour Azhari

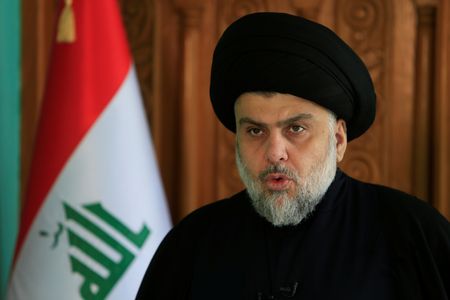

BAGHDAD (Reuters) – Less than a year after declaring he had left Iraqi politics, the unpredictable Shi’ite cleric Muqtada al-Sadr has reminded his rivals of the influence he still wields after his supporters stormed and torched the Swedish embassy in Baghdad.

Prompted by one man’s plan to burn a Koran, the incident has dragged Baghdad into a diplomatic crisis and disrupted the relative calm enjoyed by Prime Minister Mohammed Shia Al-Sudani since he took office with the backing of Sadr’s Shi’ite rivals.

While condemning the storming of the embassy, in which nobody was hurt, the Iraqi government also moved to sever ties with Sweden over the threat to burn the Koran – after Sadr challenged it to take “a firm position”.

The protester didn’t follow through with his plan to burn the Koran in Stockholm, but he still kicked and partially destroyed one. Iraq told the Swedish ambassador to leave and recalled its own envoy to Stockholm.

The issue has allowed Sadr to rally his ultra-loyal followers and points to the role he still aspires to play, even as he sits on the sidelines, having been thwarted in his bid to form a government free of his Iran-backed Shi’ite rivals.

“Sadr is asserting his powers and warning rivals that he’s still strong and stepping back from politics doesn’t necessarily mean his grip could be loosened,” said Ahmed Younis, a Baghdad-based political analyst and expert on Iraqi armed groups.

“He is still successful in using his lethal weapon against his political rivals — which is the capability of moving his popular mass base and pushing them to the street.”

A Sadr comeback could prove destabilising for Iraq, a major oil producer and a place Europe fears could become a source of more migrants if it descends into turmoil, diplomats say.

Sadr is the only Iraqi Shi’ite leader who has challenged both Iran and the U.S., a calculation that appears popular with millions of poor Shi’ites who feel they have not benefited from successive governments’ close ties to Tehran or Washington.

OUTLAW-TURNED-KINGMAKER

Sadr rose to prominence after the U.S.-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, forming a militia that waged two insurgencies against U.S.-led forces. He was an outlaw wanted dead or alive during the U.S. occupation, but later rose to become a political kingmaker and Iraq’s most powerful figure.

He is an heir to a prominent clerical dynasty. Sadr is the son of revered Grand Ayatollah Mohammed Sadeq al-Sadr, who was assassinated in 1999 after openly criticising then-dictator Saddam Hussein. His father’s cousin, Mohammed Baqir, was also killed by Saddam, in 1980.

When Saddam was executed in 2006, witnesses taunted him by chanting Moqtada’s name as he was led to the gallows, leaked footage showed.

Sadr’s movement won more seats than any other faction in legislative elections in 2018 and 2021, and many of his supporters hold key positions in the state bureaucracy.

His rivalry with Shi’ite factions backed by Iran has fuelled bouts of instability, including last year when deadly fighting erupted in Baghdad as Sadr’s attempts to form a government on his terms were thwarted.

This led Sadr to declare last August that he was withdrawing from politics, leaving the Iran-backed Shi’ite groups in the driving seat of government.

‘WE WILL NOT REMAIN SILENT’

A Shi’ite politician from one of Sadr’s rival parties said the storming of the embassy aimed to embarrass the government, and to weaken its international ties built by Sudani, who has forged good relations with Western countries including the U.S.

A politician from Sadr’s movement said his withdrawal from politics did “not and will not mean that we will not have a word and a position on issues that we consider crucial and sensitive, such as the crime of burning the Koran”.

“Those who control the current government should understand a fact: that we will not remain silent about crucial issues and … our hundreds of thousands of supporters are ready to take to the street once needed.”

Sadr has mostly laid low since announcing his departure from politics, engaging supporters in religious events rather than calling them to the streets for protests.

That has changed after the burning of a Koran in Sweden last month, when Sadr called on supporters to engage in mass demonstrations at the Swedish embassy and other parts of Iraq.

For the Sadrists, the burning of the Koran “could be an issue that could revitalize their ideological power amongst Iraqis”, said Renad Mansour, director of the Iraq Initiative at London’s Chatham House think tank.

“It also puts the government on the spot,” he said

“Although he said he was leaving politics, his intention was never really to leave politics. In fact, his goal now is to stage a comeback.”

(Writing by Tom Perry; Editing by Michael Georgy, William Maclean)